How hooked bills and heavy stomachs fuel long migrations

Great migration

The breeding grounds of northern wheatears range from Alaska and Canada in the West to Eastern Russia eastwards, but, surprisingly, the whole world population winters in Sub-Saharan Africa.

For the extreme western breeding birds, this means the challenge of making yearly migratory flights of up to 15000 km each, spanning vast tracks of open ocean. The eastern populations migrate over Siberia, resting after every 290 km on average.

Living in open habitats allows northern wheatears, just as larks, to have long wings. These wings are powered by strongly developed flight muscles attached to a large breastbone, which enable this extraordinary migratory behaviour.

The tail is relatively short and therefore does not get in the way when standing and hunting in an upright position. Its striking black-and-white pattern serves in courtship display and territory disputes.

Northern wheatears are typically found in natural or semi-natural habitats with low vegetation interspaced with open ground or boulders, like coastal dunes, heathlands, and (alpine) meadows. They breed in burrows close to the ground, like openings between tree roots, rock crevices or burrows dug by other animals, such as rabbits.

The species is declining in Europe, probably due to cultivation of breeding habitat, increased vegetation height as a result of soil enrichment or reduced grazing, and reduced insect numbers due to acidification of heathland soils.

High eyes

Their long legs, especially shinbones and tarsi, position their large eyes – compared to an average songbird – high enough to spot prey upon sight at a distance. These long legs and their heavy leg muscles support the birds when they make their way hopping or running among the vegetation. Contrastingly, forest-dwelling birds, like blackcaps or tits, which gather small insects or berries from trees and bushes, show very different legs. They have long thigh bones and short but strong lower legs, in order to climb through the foliage, grasping twigs at different angles.

Hooked tool

Northern wheatears have a variety of invertebrates on the menu, some of which can be quite large compared to the size of the bird and its mouth opening! Also, some of these prey have techniques to protect themselves, for example with strong armour, stinging hairs, or toxic stings. Wheatears often remove such shielding before eating and when preparing their prey, they make use of their hooked bill tip.

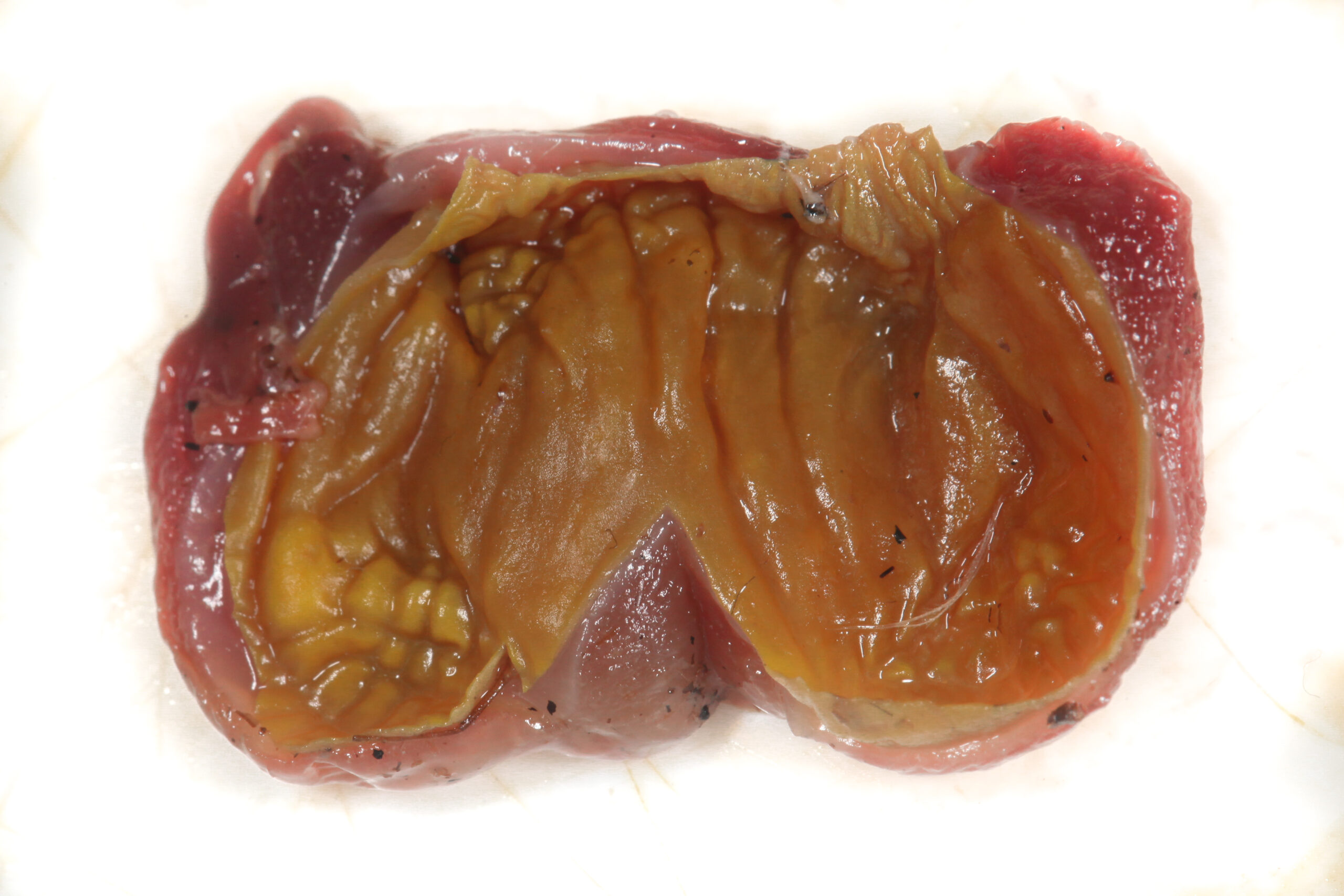

A diet like this also requires a stomach capable of crushing insect armour. Therefore, the stomach is strongly muscular and has a tough, leathery inner wall.

For comparison, the food of blackcaps hardly needs processing, reflected in a hookless bill tip (photo below) and a smaller and less muscular stomach, although the bill is relatively wide in this species in order to swallow fruits whole.

Continue reading

Large (wheat)ears

The ears of northern wheatears are large, like in many songbirds, which enable them to hear the song of potential mates or rivals, and to pick up social calls from their chicks in the nest burrow or from their partner. Although one could expect that such large ears also help in detection of insect larvae hiding in the soil, this is most likely not the case. Random noise from the environment makes it nearly impossible to detect the very subtle noises of prey movements, as was studied in thrushes. It turned out that they only use visual cues to locate earthworms in the soil.

Dependent on the habitat, northern wheatears may show variation in the exact composition of their diet. They are also known to feed at sites that concentrate insects, such as animal dung, carcasses or tidal zones. This flexibility in behaviour helps them crossing large areas of less suitable habitat, for example during migration.

In some habitats, where they feed dominantly on ground dwelling insects and their larvae, northern wheatears are prone to high levels of dioxins and PCBs in their eggs. These toxins appear to build up in soil insects, even at sites without alarming soil contamination levels.

Although the impact of this contamination on the population level (which is steeply declining) is still unknown, remarkable embryo deformities have been found in such populations.